People’s History of the Marvel Universe, Summer Special: Anti-Mutant Prejudice in the Superhero Community

Anonymous asked:

Are there any notable examples of anti-mutant prejudice towards the X-Men coming from within the superhero community?

This is a great question!

This gets to the complicated nature of how mutants fit into the Marvel Universe. I’ve always been a vocal proponent of the idea that, far from the mutant metaphor only making sense if it’s in its own little bubble where mutants are the only people with superpowers, the mutant metaphor actually functions better in the context of the Marvel Universe, because it allows you to explore more complicated and more subtle ways that prejudice functions.

While there are plenty of super-villains who have quite blatant anti-mutant prejudice, you don’t tend to get that same kind of overt bigotry towards mutants among super-heroes. Partly, this is because bigotry is a very unheroic character trait, but it also has to do with the way that the way that Marvel historically portrayed the spillover effects of anti-mutant prejudice.

Following in a kind of Niemöllerian logic, it’s almost always the case that groups that hate and fear mutants also end up hating and fearing non-mutant superheroes. Thus, Days of Future Past starts with the Sentinels being turned on mutants, but it ends with the Sentinels wiping out the Avengers and the Fantastic Four too – because the same atavistic fear of “the great replacement” applies to both mutants and mutates. Likewise, the same forces that line up to push through the Mutant Registration Act inevitably end up proposing a Superhuman Registration Act, because once you’ve violated the precepts of equality under the law for one minority group, you establish a precedent to do it to another.

Instead, I would argue what you see in the case of anti-mutant prejudice among superheroes is explorations of liberal prejudice. This takes many different forms: in Civil War, you see Tony Stark insensitively try to wave the bloody shirt of Stamford in the face of a survivor of the Genoshan genocide or Carol playing the good liberal ally but ultimately trying to get mutants to set aside their own struggle in favor of her own political project. (For someone who’s spent a good deal of time working, and living with, the X-Men, occasionally against the interests of the state, Carol does have a tendency to stick her foot in her mouth. Hence in Civil War II, you see Carol essentially goysplaining the dangers of creeping authoritarianism to Magneto.)

In Avengers vs X-Men, you see the Avengers acting like they know the Phoenix Force better than mutants and ultimately prioritizing the safety of mankind over the efforts of mutantkind to reverse their own extinction. This is where the “Avengers are cops” meme in the fandom comes from. (I would argue that Captain America is badly mischaracterized in the latter event – we know which side he’s on when the interests of mutants and the interests of the state come into conflict.)

The common thread here is that anti-mutant prejudice among superheroes emerges as a kind of unthinking, unreflective callousness brought on by a worldview that thinks of humans as the universal default of lived experience – while thinking of mutants as a somewhat annoying special interest group that fixates on their particularist grievances rather than working for what the heroes consider to be the common good.

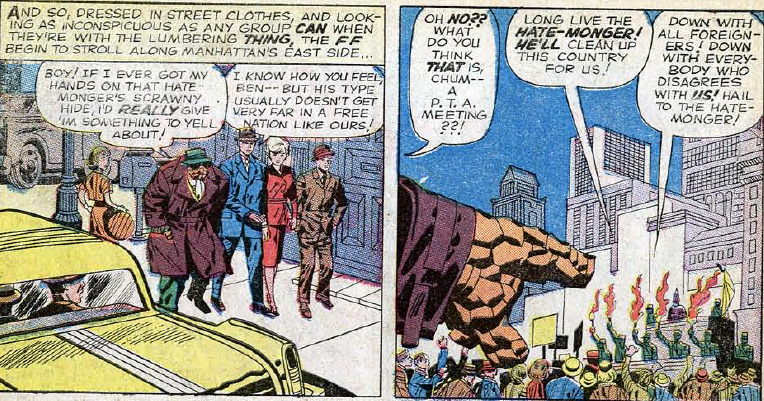

For a more intimate version of how this plays out, I think the Fantastic Four are a great exploration of how “well-meaning” liberals can massively fuck up when they don’t do the work of examining their own biases. We’ve seen this since the very beginning: in Fantastic Four #21, Kirby goes out of his way to depict uber-WASP Reed Richards blithely assuming that the “free market of ideas” will take care of the Hatemonger, while the subtextually Jewish Ben Grimm knows that the way to deal with a mind-controlling Hitler clone wearing purple Klan robes is deplatforming-by-way-of-clobberin’.

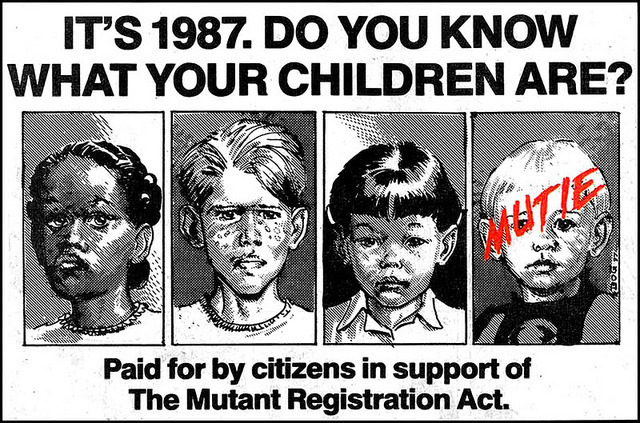

Then later on, we see Reed Richards debate Congress out of passing a Superhuman Registration Act, while saying nothing about the Mutant Registration Act – even though he has a mutant son who is directly threatened by it. (See that adorable blond moppet with the slur scrawled across his face in the fictional advertisement above? That’s Franklin Richards.) This is why I have a crack theory that Franklin’s biological father is actually Namor rather than Reed, which is why Reed so consistently shows a passive-aggressive hostility to his son’s mutancy.

At the same time, Sue also has her blindspots when it comes to mutant rights. In the underrated FF/X miniseries, Susan Storm acts like an understanding and supportive parent to Franklin – right up until someone suggests that Franklin might want to come to Krakoa and explore his mutant identity, at which point she goes full Karen and starts lashing out with her powers. Chip Zdarsky, the writer, explicitly compared Reed and Sue to liberal parents who support gay rights in the abstract until their kid comes out as trans and wants to spend time in LGBT+ spaces.

Discover more from Graphic Policy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

My feelings about the X-Men in the wider shared universe is highly mixed. Mostly in terms of aesthetic value (both sides) and overall utility.

Before 2000, it was understood that the Marvel Shared Universe was a parlor room courtesy that individually each title had its own corner and that stories in one are not germane to another. Like at its core the shared universe exists to build up brands and not to serve any larger aesthetic purpose or utility (that’s why the first-ever crossover, Secret Wars 1984 is still the best in my view). That’s why The Avengers could be big deal inside the Marvel titles but mostly mid (barring Stern’s run) to the reading public in the 80s (at a time when X-Men comics were so big that had it been siloed to its own publishing house it would be the third biggest after Marvel and DC). Ideally the Marvel Shared Universe worked best in an anarchic free for all where there wasn’t a single over-brand as it was Pre-2000s (not a big fan of the CIVIL WAR aftermath and the MCU hijacking a story that was a Pan-Marvel story like Secret Wars into the Avengers’ aegis).

— To the extent it tells a story, it leads to a kind of dance-off between which brand gets to the bigger story. Because your ideas about Franklin, in the eyes of some (not me), threaten to make the Fantastic Four into a X-Men title (which is likely the reason behind Dan Slott’s deeply petty and disingenuous retcon to keep Hickman and Zdarsky from making the Fantastic Four cool).

— The X-Men’s overall scale is so large that it can potentially subsume, (and in the past, it did subsume), the wider Marvel Universe (as in Days of Future Past). Your post does a great job explaining how the Mutant Metaphor fits within the wider Marvel Universe but that only applies if the X-Men is at the center. From the perspective of the FF or Avengers fan (which I’m not, but for the sake of devil’s advocate), the idea of their heroes being inherently flawed or weak on account of a mutant rights story from a book they might not have read doesn’t sit right with them.

— I personally think Zdarsky did a great job in blending the FF and X-Men sides that does fairly to both but Brevoort (FF editor and generally speaking deeply conservative and tradition in terms of brand hierarchies of 616) and Slott didn’t get the memo.

The Marvel Shared Universe isn’t quite there on the level of the Greek Myth where the Argonautica tells a story about Jason and Medea but doesn’t subsume the stories of Heracles and others who accompanied him. Heracles an

d his myth isn’t shafted to make Jason look good and the aftermath of Jason and Medea doesn’t drag down the former. So I personally do think the X-Men working by themselves apart from the wider 616 is a strength. Not that I’m militating against it either way.